Americana

Classics from across the pond

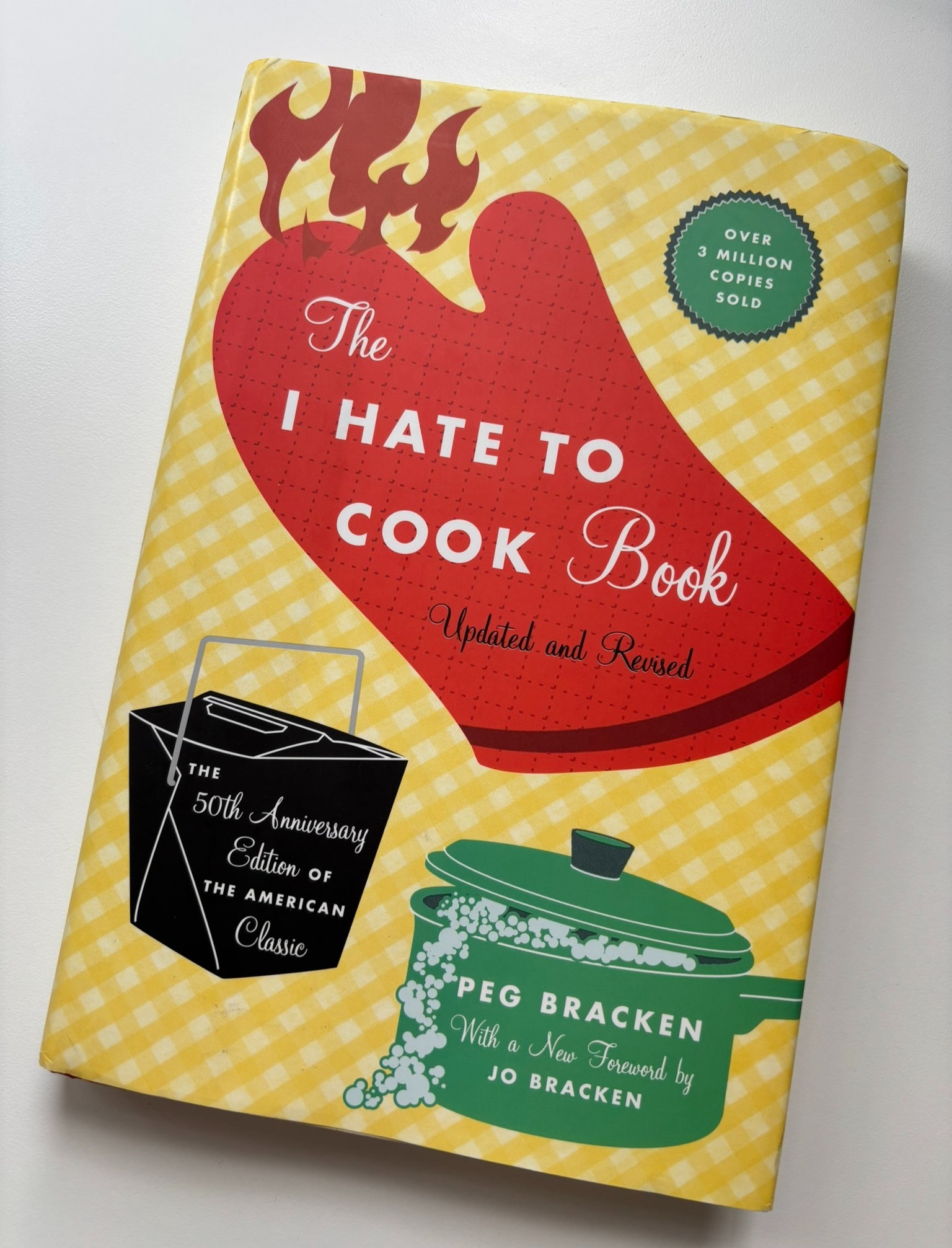

The I Hate to Cook Book Peg Bracken Grand Central Publishing 2010

coming soon ...

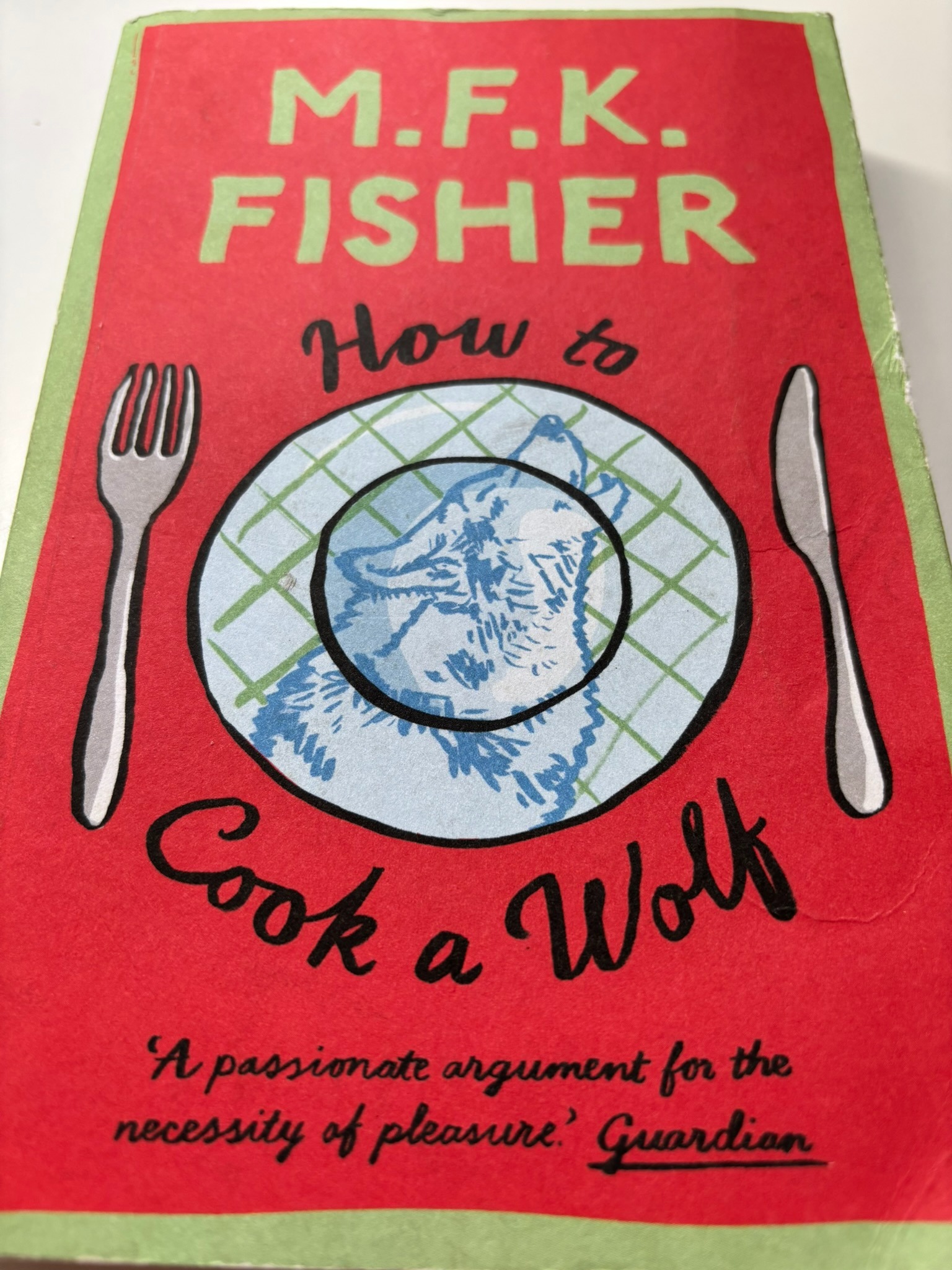

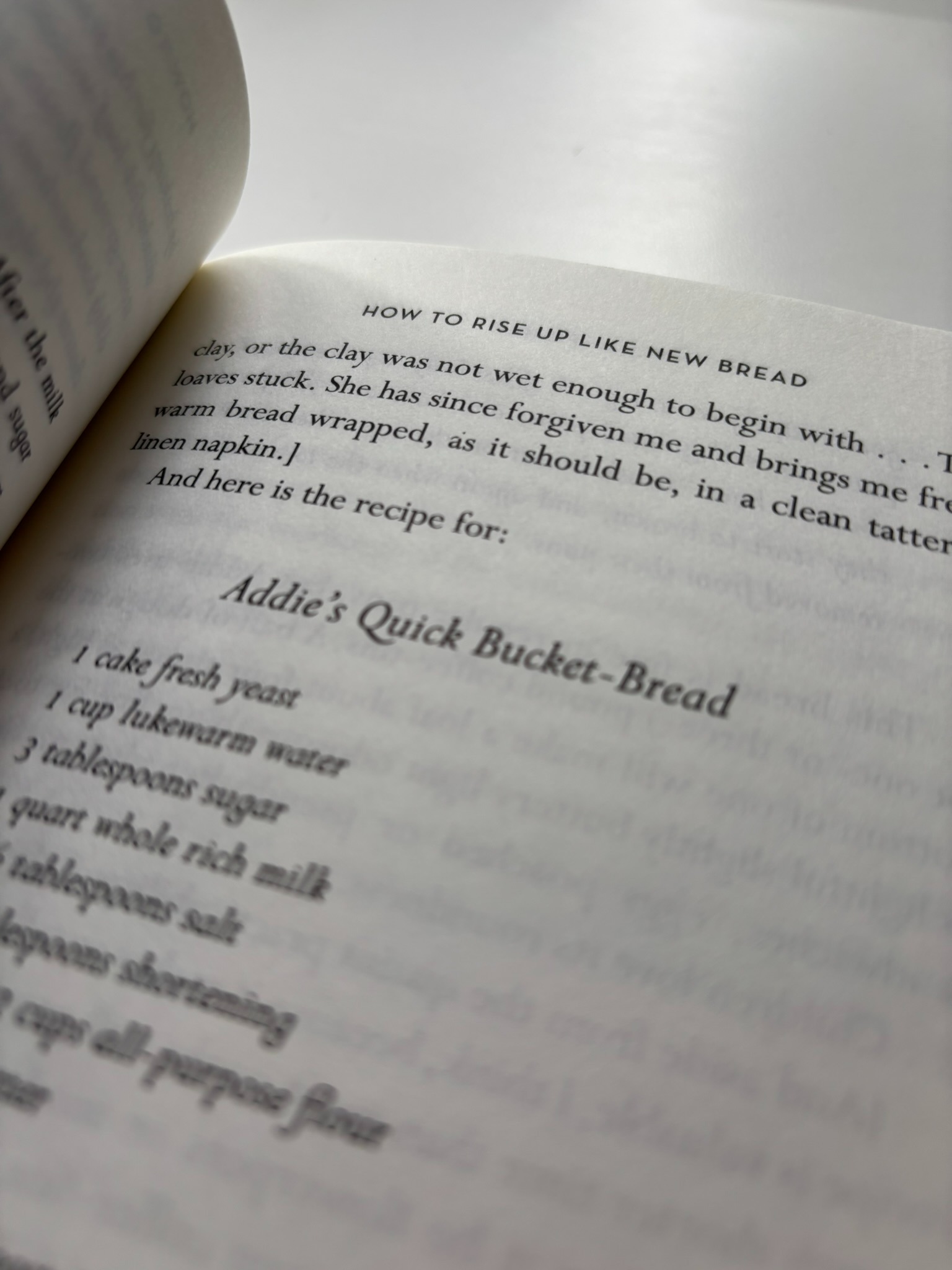

How to Cook a Wolf MFK Fisher Daunt Books 2020

a slightly Lovecraftian feel to it, something from the depths of space and time whose presence at the supper table could only be the harbinger of cosmic doom or some such ...

‘Aunt Gwen’s Cold Shape’, p129, is a marvellously titled dish. I’ve always felt it had a slightly Lovecraftian feel to it, something from the depths of space and time whose presence at the supper table could only be the harbinger of cosmic doom or some such. Lord knows who Aunt Gwen was (a family friend rather than blood, apparently) but she clearly wasn’t one for impressing with the nomenclature of her dishes. Bring forth the Cold Shape I hear her cry in my darkest moments, oh and a bit of that nice watercress we picked yesterday … even the recipe, somewhat apologetically, insists it be served with cucumber-chips as if they might somehow cover its obscene, wobbly nakedness.

Things get little better as you read on through the recipe: ‘1 calf head’ is daunting enough but when followed by the qualification ‘quartered’ it becomes entirely nightmarish. Then, ‘remove most of fat, and the brains, ears, eyes and snout’. Good grief. Little else is involved baring some basic seasoning and white wine: one glass for the pot and the rest of the bottle for the hapless chef one suspects (followed by serious consideration as to whether an omelette might be preferable for that night’s meal). It’s a cousin of good old Tête de Veau, of course (how much nicer things sound in French). She describes her own encounter with La tête as a child on the preceding page, this time halved, in a vivid, disturbing and fascinatingly macabre slice of prose. You’ll simply have to read it for yourself although I can’t resist mentioning the eye closed in its ‘savoury wink’. A inimitable phrase, and one not easily forgotten.

It's typical of an author as clearly in love with language as with food. There’s nothing in the vocabulary, prosody, syntax, phraseology of her writing that suggests anything other than full control, unless she writes it wild and unsaddled as on occasion seems to be wish. Radical, candid and risky especially for a woman writing in that time. Her ostensibly domestic subject matter might seem becoming but she uses it to devasting affect, the writing of it lithe, muscular and yet deeply sensitive in a way that is entirely genderless. It's something reflected in her own ambiguous name: three initials and a rather plain surname that gives little away as to gender, background or ancestry. But it does have a nice rhythm to it – MFK Fisher – a rush of initials, a slight hanging pause and into the declarative first syllable that resolves into the minor key of the second. Delicious on the ear and in the mouth. Despite its male, ivy-league, professorial suggestiveness, the initials stood for Mary Frances Kennedy. Kennedy was her maiden name, Fisher being picked up and retained post-marriage and indeed post-divorce.

to be continued ...